NetChoice v. Paxton Redux: Algorithm Disclosure

Postscript.

Oops. I just downloaded the Amended Complaint in NetChoice v. Paxton, and I see that NetChoice has granted everything I ask for below. My intended amicus brief is obsolete before it is born. I haven’t seen any sign that the Western District’s preliminary injunction has been amended, but it should be, since NetChoice is no longer asking to enjoin the algorithm disclosure mandate and other provisions in Texas Code §§120.051-053.1

This is pretty big news, though, and I wonder why nobody is talking about. At last we get to see exactly how X prioritizes posts! Or, X will stall by making a vague and useless disclosure, upon which the Texas Attorney General will have to sue them.

Introduction

Texas law HB 20 contains various provisions of which the best known is that large internet platforms not discriminate among users on the basis of viewpoint:

Sec. 143A.002. CENSORSHIP PROHIBITED. (a) A social media platform may not censor a user, a user's expression, or a user's ability to receive the expression of another person based on: (1) the viewpoint of the user or another person . . .

The platforms— X, Facebook, You-Tube, and so forth— sued, saying that not being able to censor users violated their First Amendment right to free speech, since it forced them to allow people to say things on their platforms they didn’t agree with. The issue is whether X is more like a magazine or a phone company. Texas can’t force a transmit his conversations. I wrote an amicus brief using economic arguments to say X is more like a phone company, as a natural monopoly and a common carrier. In 2024, this went to the Supreme Court, which seems to disagree but which said that it was hard to tell given the facts available, so the case was not ready for Supreme Court review and should have the facts developed more, at the level of the one-judge District Court. So they sent it back to the original judge where the case was first filed.

The case is in process where it was first filed, at the Western District of Texas federal court. I won’t address the big issue of viewpoint discrimination here, though. Instead, I’ll talk about HB 20’s required disclosure of the platform’s moderating policy (“algorithm disclosure”).2

“Algorithm” refers to the computer code or other method the platform uses to decide which posts to show a user. Let’s assume that the platform in question is Elon Musk’s X, the former Twitter, and that X can discriminate on the basis of political view, as the Supreme Court has implied. It can ban all Democrats, for example, or, given Musk’s evolution, all Democrats plus everyone in the Trump Administration.3 More mildly, it could throttle the posts, putting them far down on the list of posts in a user’s feed, or only showing them to a few users, or only showing them late at night.4 X already throttles posts, mostly in ways the public doesn’t know.

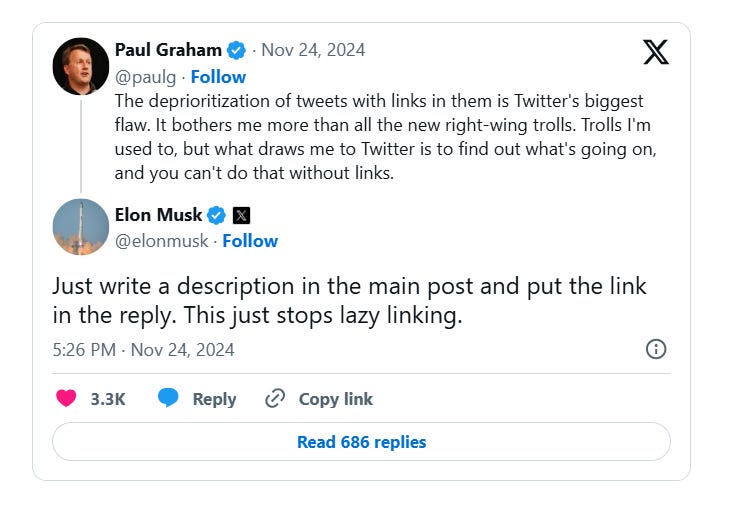

Figure 1 shows a way we do know, as a result of user observations confirmed by that exchange between Paul Graham and Elon Musk: if you put a link to a magazine article in your post, X will put it lower in priority, and fewer users will see it. Musks says to put your link in a comment to your own post, instead. Many users hate this. I, myself, do. The kind of post I like best is one that says something interesting and links to its source so I can verify it and read more. But I see why Musk, as owner of X, doesn’t like that. He wants me to stay on X and read more X posts, not go off and spend time at Substack or the Wall Street Journal. It’s his company, not mine, so if I want links in posts I have to go to Bluesky, even though it’s worse than X in other ways. And even if the Supreme Court upholds the Texas law, Musk can set his algorithm to throttle posts with links, since that’s not discrimination based on viewpoint.5

But let’s assume the Supreme Court strikes down the ban on viewpoint discrimination. It could still uphold HB 20’s requirement that platforms disclose their algorithms. The algorithm disclosure part of HB 20 says,6

Sec. 120.051. PUBLIC DISCLOSURES.

(a) A social media platform shall, in accordance with this subchapter, publicly disclose accurate information regarding its content management, data management, and business practices, including specific information regarding the manner in which the social media platform:

(1) curates and targets content to users;

(2) places and promotes content, services, and products, including its own content, services, and products;

(3) moderates content;

(4) uses search, ranking, or other algorithms or procedures that determine results on the platform . . .

This is good product-disclosure policy. Whether you think X is a natural monopoly or is in tight competition with very similar products, it’s good for customers to know what they’re getting. In many, many parts of the economy, we have regulations that even free marketeers thinks is good: requirements that companies honestly describe their products so consumers can make informed choices. Companies, especially new entrants, can only compete by charging low prices if customers can be sure they’re not lying about their quality.

In the case of X, both readers and writers want to know what makes a post get broad readership, so they want to know about the algorithm. They don’t want to see every detail, but writers want to know how to get people to read their posts, and readers want to know what they might be missing because of platform censorship. I am both a writer and a reader myself. If the algorithm says, “Put posts by Eric Rasmusen at level 5 out of 6,” I want to know. I don’t want to post into the void, so I won’t bother posting so much and maybe I’ll switch to Bluesky. If it says, “Put posts that use the word ‘marginal’ at level 5,” I’ll switch to other words. And as a reader, I’d like to know if it says, “Put posts by Steve Sailer at level 6,” because then I’ll go directly to Sailer’s timeline so I can see everything he’s posting. And if it says, “Put posts critical of the Chinese goverment at level 4,” I’ll know that X is a biased source for news about China, and perhaps X is even being paid by the Communist Party to throttle criticism.

In fact, it’s possible that knowledge of Twitter’s moderation policy is what made Elon Musk buy it and change its name to X. Twitter banned posts by The Babylon Bee, an irreverent and very funny humor website. Anyone who saw that happen could tell that profitability was not the priority for Twitter: they were banning a popular account that must have had users viewing lots of ads, so they were putting employee ideology over shareholder profits. In addition, Twitter had a very large number of individual people as moderators. Algorithms aren’t entirely computer-driven: one algorithm is, “Throttle anything that employees Dolores Ratched or Mildred Umbridge thinks is offensive.”7 People are more expensive than computer code, though, and so these employees were likely generating negative value but still being paid positive salaries to advance the ideological agendas of senior management. Seeing that Twitter was sacrificing revenue and inflating costs made it a tempting takeover target, even aside from any noble motives Elon Musk may have had.8

Thus, there is ample reason for 120.051 as a consumer protection law, even without the anti-discrimination parts of HB 20. It would be like a multitude of other laws and regulations that require disclosure of product quality without requiring the quality to be of any particular level.

The Legal Analyis Summarized

The rest of this Substack is concerned with what the courts should do about algorithm disclosure. They have actually done almost everything by now, except for the crucial final step. The 5th Circuit Court of Appeals and the U.S. Supreme Court have made no objection to its constitutionality. Even if enforcement of the rest of HB 20 is prevented by preliminary injunction, the algorithm disclosure provision should not be. section 12.0151 is easily severable from the rest of HB 20, as are the uncontroversial provisions 120.052 (disclose acceptable uses) and 120.053 (report certain statistics biannually).'

It seems both parties acknowledge this. A footnote in the 5th Circuit opinion of Nov. 7, 2024 (on remand from the Supreme Court) says,

We previously held that the “one-and-done” disclosures and the “biannual transparency-report requirement” were facially constitutional, and the Supreme Court did not review that decision. See NetChoice, LLC v. Paxton, 49 F.4th 439, 485–86 (5th Cir. 2022). The parties correctly agree that holding still binds the district court on remand. See Supp. Br. of Appellant (Texas) at 9–10; Supp. Br. of Plaintiffs–Appellees at 3 n.2.

But the District Court’s preliminary injunction of December 1, 2021 says,

IT IS FURTHER ORDERED that Plaintiffs’ motion for preliminary injunction, (Dkt. 12), is GRANTED. Until the Court enters judgment in this case, the Texas Attorney General is ENJOINED from enforcing Section 2 and Section 7 of HB 20 against Plaintiffs and their members.

Why is that preliminary injunction still in place?9 It should be amended to say,

IT IS ORDERED that Plaintiffs’ motion for preliminary injunction, (Dkt. 12), be GRANTED in part. Until the Court enters judgment in this case, the Texas Attorney General is ENJOINED from enforcing Sections 2 and 7 of HB 20 (with the exception of 120.051, 120.052 and 120.053) against Plaintiffs and their members.

This modification should be made immediately, and the Attorney General should start discussions with the platforms as to a reasonable deadline for them to comply.

History: The District Court

The brief legal analysis of the last section is really enough, but let’s go through the history of the courts’ involvement. Texas law HB 20 was temporarily enjoined by the Western District of Texas. The 5th Circuit reversed. The Supreme Court took up the case in conjunction with Moody v. NetChoice, which concerns a similar Florida law and district court preliminary injunction upheld by the 11th Circuit.

The Western District of Texas granted the preliminary injunction on December 1, 2021 in case 1:21-CV-840-RP. The opinion has only two mentions of algorithm disclosure. The first mention merely describes the statute.10 The second says,11

Plaintiffs also express a concern that revealing “algorithms or procedures that determine results on the platform” may reveal trade secrets or confidential and competitively-sensitive information. (Id. at 34) (quoting Tex. Bus. & Com. Code § 120.051(a)(4)).

This is just a mention of a plaintiff argument, without either assent or rejection by the Court. And in fact the Court never refers to it again, only to constittional arguments, and those not in application to algorithm disclosure.

Trade secret? Why would a platform want to conceal its moderation pratices from competitiors? Customers, yes, to trick them into thinking they have a fair shot with their posts getting attention, or to conceal political bias. Perhaps there are also some programming tricks; those could be concealed if their effect is revealed. “Pseudo-code” is the name for generic, simplified code of no partiular langugae such as Fortran or Python, to illustrate what program is intended to do. It is a bit like making a legal argument without any actual case or statute quotes or exact citation, just to show what the real argument would look like. The project manager might write pseudo-code for his dozen employees to put into Python.

On disclosure generally, the District Court said,

To pass constitutional muster, disclosure requirements like these must require only “factual and noncontroversial information” and cannot be “unjustified or unduly burdensome.” NIFLA, 138 S. Ct. at 2372. Section 2’s disclosure and operational provisions are inordinately burdensome given the unfathomably large numbers of posts on these sites and apps. For example, in three months in 2021, Facebook removed 8.8 million pieces of “bullying and harassment content,” 9.8 million pieces of “organized hate content,” and 25.2 million pieces of “hate speech content.” (CCIA Decl., Dkt. 12-1, at 15). . . . For example, in a three-month period in 2021, YouTube removed 1.16 billion comments. (YouTube Decl., Dkt. 12-3, at 23–24). Those 1.16 billion removals were not appealable, but, under HB 20, they would have to be. (Id.).

Algorithm disclosure is not subject to that problem— there are no appeals. The Court is talking about explaining removals. The algorithm is the same size regardless of the number of users.

The Section 2 requirements burden First Amendment expression by “forc[ing] elements of civil society to speak when they otherwise would have refrained.” Washington Post v. McManus, 944 F.3d 506, 514 (4th Cir. 2019). “It is the presence of compulsion from the state itself that compromises the First Amendment.” Id. at 515. The provisions also impose unduly burdensome disclosure requirements on social media platforms “that will chill their protected speech.” NIFLA, 138 S. Ct. at 2378. The consequences of noncompliance also chill the social media platforms’ speech and application of their content moderation policies and user agreements. Noncompliance can subject social media platforms to serious consequences. The Texas Attorney General may seek injunctive relief and collect attorney’s fees and “reasonable investigative costs” if successful in obtaining injunctive relief. Id. § 120.151.

We do not say a cereal box ingredients are compelled speech, or SEC filings. The dislosure is not very burdensome— the platforms are not required to write up new documents as with most regulatory filings; they just have to make public the moderation rules they already give their employees for internal use. They may well be ashamed of those rules, but so many the cereal company or the corporation that has a sharp earnings drop. Indeed, these very corporations already are subject to SEC disclosure requirements. Note that enforcement is by injunction and attorney fees, not by fines or imprisonment. And this is a lot less onerous than most regulation, e.g. SEC filings.

The platforms also objected that the algorithm disclosure requirement was so vague that they’d have no idea how to comply with it, so it would be unfair to punish them by subjecting them to the possibility that the Attorney General might sue them and make them pay his attorney’s fees. The Court rejected that argument:

Plaintiffs contend that Section 2’s disclosure and operational requirements are overbroad and vague. “For instance, H.B. 20’s non-exhaustive list of disclosure requirements grants the Attorney General substantial discretion to sue based on a covered platform’s failure to include unenumerated information.” (Id.). While the Court agrees that these provisions may suffer from infirmities, the Court cannot at this time find them unconstitutionally vague on their face.

And that is correct. The algorithm disclosure provision is not too vague. HB 20 is certainly no less clear than the average federal statute on which regulations are based. Consider the most important anti-monopoly law, the Sherman Act, 15 US Code 1:

Every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, is declared to be illegal. Every person who shall make any contract or engage in any combination or conspiracy hereby declared to be illegal shall be deemed guilty of a felony, and, on conviction thereof, shall be punished by fine not exceeding $100,000,000 if a corporation, or, if any other person, $1,000,000, or by imprisonment not exceeding 10 years, or by both said punishments, in the discretion of the court.

What is a contract “in restraint of trade or commerce”? The intent of the law was to criminalize contracts between companies to keep prices high, which would diminish the quantity sold; or contracts where they split up the market and agreed not to compete with each other, but there are lots of unfair business practices that the law might encompass. Yet courts have upheld the Sherman Act, which unlike HB 20 is a criminal statute enforced by prison terms, against the challenge that it was void for vagueness.12

History: The 5th Circuit

The 5th Circuit said in Case 21-51178 on September 16, 2021,

Section 2 requires the Platforms to make certain disclosures that consist of “purely factual and uncontroversial information” about the Platforms’ services. Zauderer v. Off. of Disciplinary Couns., 471 U.S. 626, 651 (1985).

The opinion discusses algorithm disclosure at length.

The Platforms all but concede that publishing an acceptable use policy and high-level descriptions of their content and data management practices are not themselves unduly burdensome. Instead, they speculate that Texas will use these disclosure requirements to file unduly burdensome lawsuits seeking an unreasonably intrusive level of detail regarding, for example, the Platforms’ proprietary algorithms. But the Platforms have no authority suggesting the fear of litigation can render disclosure requirements unconstitutional—let alone that the fear of hypothetical litigation can do so in a pre-enforcement posture.

I think the platforms are correct that a plain reading of the HB 20 could require disclosure of their proprietary algorithms, or at least of the effect of those algorithms if not the specific, proprietary, coding methods. When it requires “specific information regarding the manner in which the social media platform uses search, ranking, or other algorithms or procedures that determine results on the platform,” HB 20 is not just just asking the platform to say Yes or No. This does not allow for a facial challenge though. Whether it is too burdensome can only be litigated once a dispute arises over whether HB 20 requires disclosure of the algorithms. This is the sort of thing done by regulations all the time.

There is further problem:

The Platforms’ argument ignores the fact that under Zauderer, we must evaluate whether disclosure requirements are “unduly burdensome” by reference to whether they threaten to “chill[] protected commercial speech.” 471 U.S. at 651. That is, Zauderer does not countenance a broad inquiry into whether disclosure requirements are “unduly burdensome” in some abstract sense, but instead instructs us to consider whether they unduly burden (or “chill”) protected speech and thereby intrude on an entity’s First Amendment speech rights.36 Here, the Platforms do not explain how the one-and-done disclosure requirements—or even the prospect of litigation to enforce those requirements—could or would burden the Platforms’ protected speech, even assuming that their censorship constitutes protected speech.

The partial concurrence of Judge Edith Jones does not disagree. Her concerns are with Section 7, the discrimination section:

First, some points of agreement. As to the discussion of the First Amendment, the majority is certainly correct that a successful facial challenge to a state law is difficult. Consequently, I agree that a facial challenge to the Disclosure and Operations provisions in Section 2 of HB 20 is unlikely to succeed on the merits. These portions of the law ought not to be enjoined at the preliminary injunction stage. . . .

My disagreement with my colleagues lies in the application of First Amendment principles to the anti-discrimination provisions of Section 7.

So we just need to ask if the algorithm disclosure part of the 5th Circuit opinion has been overruled by the Supreme Court.

History: The Supreme Court

On July 1, 2024, the U.S. Supreme Court issued an opinion in Moody v. NetChoice, with which Paxton v. NetChoice had been consolidated. The majority opinion made no mention of algorithm disclosure. It focusses on 1st Amendment issues of whether content moderation was expressive, and on as-applied versus facial challenges. It criticizes the 5th Circuit decision, but only in those respects:

The Fifth Circuit was wrong in concluding that Texas’s restrictions on the platforms’ selection, ordering, and labeling of third-party posts do not interfere with expression. And the court was wrong to treat as valid Texas’s interest in changing the content of the platforms’ feeds.

and

In reviewing the District Court’s preliminary injunction, the Fifth Circuit got its likelihood-of-success finding wrong. Texas is not likely to succeed in enforcing its law against the platforms’ application of their content-moderation policies to the feeds that were the focus of the proceedings below. And that is because of the core teaching elaborated in the above-summarized decisions: The government may not, in supposed pursuit of better expressive balance, alter a private speaker’s own editorial choices about the mix of speech it wants to convey.

The two concurrences by Justice Barrett and Jackson similarly ignore algorithm disclosure and focus on facial vs. as-applied challenges. Justice Thomas’s concurrence merely says that he wishes the Court to reconsider Zauderer.13 Justice Alito says in his concurrence with Justices Thomas and Gorsuch that,

NetChoice argues in passing that it cannot tell us how its members moderate content be cause doing so would embolden “malicious actors” and divulge “proprietary and closely held” information. E.g., Brief for Petitioners in No. 22–555, at 11. But these harms are far from inevitable. Various platforms already make similar disclosures—both voluntarily and to comply with the European Union’s Digital Services Act —yet the sky has not fallen. And on remand, NetChoice will have the opportunity to contest whether particular disclosures are necessary and whether any relevant materials should be filed under seal.

and

These disclosures suggest that platforms can say some thing about their content-moderation practices without enabling malicious actors or disclosing proprietary information. They also suggest that not all platforms curate all third-party content in an inherently expressive way. With out more information about how regulated platforms moderate content, it is not possible to determine whether these laws lack “a ‘ “plainly legitimate sweep.”’” Washington State Grange, 552 U. S., at 449. For all these reasons, NetChoice failed to establish whether the content-moderation provisions violate the First Amendment on their face.

To this list can be added X’s partial reveal of its code. See “Bird’s Eye View: The Limits of Twitter’s Algorithm Release,” Gabriel Nicholas, Center for Democracy and Technology https://cdt.org/insights/birds-eye-view-the-limits-of-twitters-algorithm-release/ (April 26, 2023).

Conclusion

The 5th Circuit overruled the trial court’s preliminary injunction as far as algorithm disclosure is concerned, and the U.S. Supreme Court did nothing to alter that part of the 5th Circuit’s opinion. This means that the trial court ought to follow the 5th Circuit and modify the preliminary injunction to exclude the Texas Code sections that implement Section 2 of HB 20: algorithm disclosure, 120.051; disclosing “acceptable use” policy, 120.052; and biannual reporting of various statistics, 120.053 . Not only is removing the injunction from these sections the correct result, it also clears the ground for the real battles, which are over the burden of answering complaints, and whether or how the free speech rights of the platforms outweigh the free speech rights of the users.14

I have previous posts on Netscape v. Paxton:

The Paxton v. Netchoice Stay Application As an Example of Clever Lawyering and Bad Procedure (2022)

How the Ellsberg Paradox and Unknown Unknowns Apply to the Supreme Court's Stay Grant in NetChoice v. Paxton (TechLords v. Texas) (2022)

A Fisking of the 11th Circuit Opinion in Florida vs. Big Tech (Netchoice v. Moody (2022)

My amicus brief at the U.S. Supreme Court, on the 1st Amendment issue, natural monopoly, and common carriers.

Upcoming Posts (Previews for comment before I publish)

Footnotes

From the 2025 First Amended Complaint:

Plaintiffs’ First Amended Complaint only challenges specific provisions of HB20: HB20 Section 7 (Tex. Civ. Prac. & Rem. Code §§ 143A.001-.008) and a subset of HB20 Section 2 (Tex. Bus. & Com. Code §§ 120.101-.104). When this Complaint uses “HB20,” therefore, it refers to these challenged provisions of HB20 and not other provisions of HB20.

The 5th Circuit called algorithm disclosure “one-and-done”. I prefer “algorithm disclosure” because it conveys what must be disclosed and because the requirement is not really one-and-done: it must be updated regularly. The platform’s algorithm changes continually in small ways, and the disclosure would have to be repeated at reasonabl intervals, e.g. annually. The 5th Circuit says,

First, there are what we will call the “one-and-done” disclosures: requirements to publish an acceptable use policy and disclose certain information about the Platforms’ content management and business practices. See Tex. Bus. & Com. Code §§ 120.051–52.

HB 20 Section 1 says,

(3) social media platforms function as common carriers, are affected with a public interest, are central public forums for public debate, and have enjoyed governmental support in the United States; and

(4) social media platforms with the largest number of users are common carriers by virtue of their market dominance.

But the Supreme Court has suggested that internet platforms are not common carriers. But see Yoo, Christopher S., "The First Amendment, Common Carriers, and Public Accommodations: Net Neutrality, Digital Platforms, and Privacy" (2021). https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship/2576; and “Common Carrier Law in the 21st Century,” Tennessee Law Review, Forthcoming Adam Candeub.

The Supreme Court said,

If Texas’s law is enforced, the platforms could not—as they in fact do now—disfavor posts because they:

support Nazi ideology;

advocate for terrorism;

espouse racism, Islamophobia, or anti-Semitism;

glorify rape or other gender-based violence;

encourage teenage suicide and self-injury;

discourage the use of vaccines;

advise phony treatments for diseases;

advance false claims of election fraud.

We can rewrite this as

If Texas’s law is enforced, the platforms could not disfavor posts because they:

criticize Nazi ideology;

advocate against terrorism;

oppose racism, Islamophobia, or anti-Semitism;

oppose rape or other gender-based violence;

discourage teenage suicide and self-injury;

encourage the use of vaccines;

debunk phony treatments for diseases;

reveal true claims of election fraud.

or

If Texas’s law is enforced, the platforms could not favor posts because they:

support Nazi ideology;

advocate for terrorism;

espouse racism, Islamophobia, or anti-Semitism;

glorify rape or other gender-based violence;

encourage teenage suicide and self-injury;

discourage the use of vaccines;

advise phony treatments for diseases;

advance false claims of election fraud.

X has disclosed quite a bit of its algorithm, but not all of it. “Bird’s Eye View: The Limits of Twitter’s Algorithm Release,” Gabriel Nicholas, Center for Democracy and Technology (April 26, 2023).

In the Texas code, 120.051 is the algorithm disclosures. 120.052 is about disclosing the “acceptable use” policy. 120.053 requires biannual reporting of various statistics.

SUBCHAPTER B. DISCLOSURE REQUIREMENTS

Sec. 120.051. PUBLIC DISCLOSURES. (a) A social media

platform shall, in accordance with this subchapter, publicly

disclose accurate information regarding its content management,

data management, and business practices, including specific

information regarding the manner in which the social media

platform:

(1) curates and targets content to users;

(2) places and promotes content, services, and

products, including its own content, services, and products;

(3) moderates content;

(4) uses search, ranking, or other algorithms or

procedures that determine results on the platform; and

(5) provides users' performance data on the use of the

platform and its products and services.

(b) The disclosure required by Subsection (a) must be

sufficient to enable users to make an informed choice regarding the

purchase of or use of access to or services from the platform.

(c) A social media platform shall publish the disclosure

required by Subsection (a) on an Internet website that is easily

accessible by the public.

Sec. 120.052. ACCEPTABLE USE POLICY. (a) A social media

platform shall publish an acceptable use policy in a location that

is easily accessible to a user.

(b) A social media platform's acceptable use policy must:

(1) reasonably inform users about the types of content

allowed on the social media platform;

(2) explain the steps the social media platform will

take to ensure content complies with the policy;

(3) explain the means by which users can notify the

social media platform of content that potentially violates the

acceptable use policy, illegal content, or illegal activity, which

includes:

(A) an e-mail address or relevant complaint

intake mechanism to handle user complaints; and

(B) a complaint system described by Subchapter C;

and

(4) include publication of a biannual transparency

report outlining actions taken to enforce the policy.I should think that to satisfy HB 20’s algorithm disclosure requirement, saying that employees Ratched and Umbridge had discretion would be sufficient. A company is allowed to make use of humans as well as machines.

To be sure, Musk tried to get out of the acquisition later. That, however, was the result of a sharp decline in the stock market between the handshake and the closing of the deal, so Musk saw that if he could end the deal and then immediately make a new offer, he could pay far less. Naturally, the courts would not let him do this.

The District Court’s preliminary injunction is still in place, it seems, because the Supreme Court says,

We accordingly vacate the judgments of the Courts of Appeals for the Fifth and Eleventh Circuits and remand the cases for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

This vacated the lifting of the preliminary injunction by the Fifth Circuit.

The District Court says,

Section 2 requires platforms to publish “acceptable use policies,” set up an “easily accessible” complaint system, produce a “biannual transparency report,” and “publicly disclose accurate information regarding its content management, data management, and business practices, including specific information regarding how the social media platform: (i) curates and targets content to users; (ii) places and promotes content, services, and products, including its own content, services, and products; (iii) moderates content; (iv) uses search, ranking, or other algorithms or procedures that determine results on the platform; and (v) provides users’ performance data on the use of the platform and its products and services.” Id. § 120.051(a).

The District Court did obliquely allude to disclosure— though it probably meant the complaint process— in a paragraph on severability:

HB 20’s Severability Clause HB 20’s severability clause does not save HB 20 from facial invalidation. This Court has found Sections 2 and 7 to be unlawful. Both sections are replete with constitutional defects, including unconstitutional content- and speaker-based infringement on editorial discretion and onerously burdensome disclosure and operational requirements. Like the Florida statute, “[t]here is nothing that could be severed and survive.” NetChoice, 2021 WL 2690876, at *11.

This is mystifying, since it would be very easy to sever 20.051, 20.052, and 20.053. Any one of the three makes sense as stand-alone policy; each has a different objective and they could well have been separate bills instead of being combined and then combined with the ban on viewpoint discrimination.

Nash v. United States, 229 U.S. 373 (1913). Matthew Sipe disagrees and presents arguments that the vagueness doctrine has changed in “The Sherman Act and Avoiding Void-for-Vagueness,” Florida State University Law Review, 45: 709 (2018).

The District Court’s first mention of algorithm disclosure is this:

HB 20 states that each platform must disclose how it “(1) curates and targets content to users; (2) places and promotes content, services, and products, including its own content, services, and products; (3) moderates content; [and] (4) uses search, ranking, or other algorithms or procedures that determine results on the platform[.]” Id. § 120.051(a)(1)–(4).

Things to use in revision: NetChoice v. Ellison, CASE 0:25-cv-02741 Filed 06/30/25. Complaint. USDC (Minnesota).

Asserting algorithm disclosure could even conceivably be one-and-done is the weirdest part of this situation.